Whale collision in the Atlantic

Approximately 400 nautical miles west of Lisbon, there was a bang under the port hull of the catamaran…

By Rainer Holtorff (Skipper of the Catana 431)

It was shortly before sunset. Dinner was coming up. It was my watch. The north-northeast wind was blowing at force 6, causing three-meter waves to roll towards us. We had reduced to the 2nd reef in the mainsail, with only half the headsail out. We were making good progress, the log repeatedly shooting up to over 10 knots.

We had left Nantucket over 3 weeks ago, the Azores 3 days ago. Since then, we had had plenty of wind, mostly from ahead. There was no shipping traffic. There was nothing to see in front of us except waves.

Out of nowhere, there was a bang. We had taken many hits from waves on this trip, but this one was duller, more violent. The starboard bow was lifted and lowered again. Everyone rushed into the cockpit and saw the huge animal in our stern water. A sperm whale. Across the ship. It kept blowing, appearing battered, hit. For a second, I thought we could go back. But what could we do? And what would the whale do to us? Soon it disappeared astern, the yacht had picked up speed again, moving away with us. We ran forward to see if the hull was damaged, but couldn’t see anything. Looked in the forepeak, but it was dry. We sat down and ate. It wasn’t until during the meal that I realized that we had checked the bow – but maybe there was something at the stern – I checked the engine room on starboard and was horrified to find that the water was already sloshing around the engine. Although the bilge pump was running at full speed, the water began to rise down there. We cleaned the filter, but it didn’t help: the pump was running hot, seemed to be pumping nothing. We hoped that the water would only rise to the outer waterline, but it rose higher. We noticed that it was running through cable ducts, about half a meter from the floor, into the front part of the float, where the living area is located. First just a few drops, then a trickle. Finally, it was literally pressing through there. I tried to seal the passage by driving things into it with all my might, but to no avail: the water increased. The bilge pump, which was supposed to empty this part, failed after a short time. We cleaned the filter, but this didn’t help either. The manual pump, which was also there, drew air. No matter how much we pumped, it simply didn’t pump anything. I reached for the satellite phone and reached Bremen Rescue – the maritime emergency control center for ships under the German flag. I pointed out that this was not a Mayday, not yet, just a call. My contact inquired whether we had life jackets. I replied that we were almost 400 miles offshore, then the connection broke off. A little later, the Portuguese Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre, MRCC Lisboa, reported. I didn’t have much hope that we would prevent the yacht from filling up with water. We still had pretty rough seas. And the weather forecast did not promise any calming for the coming days, quite the contrary.

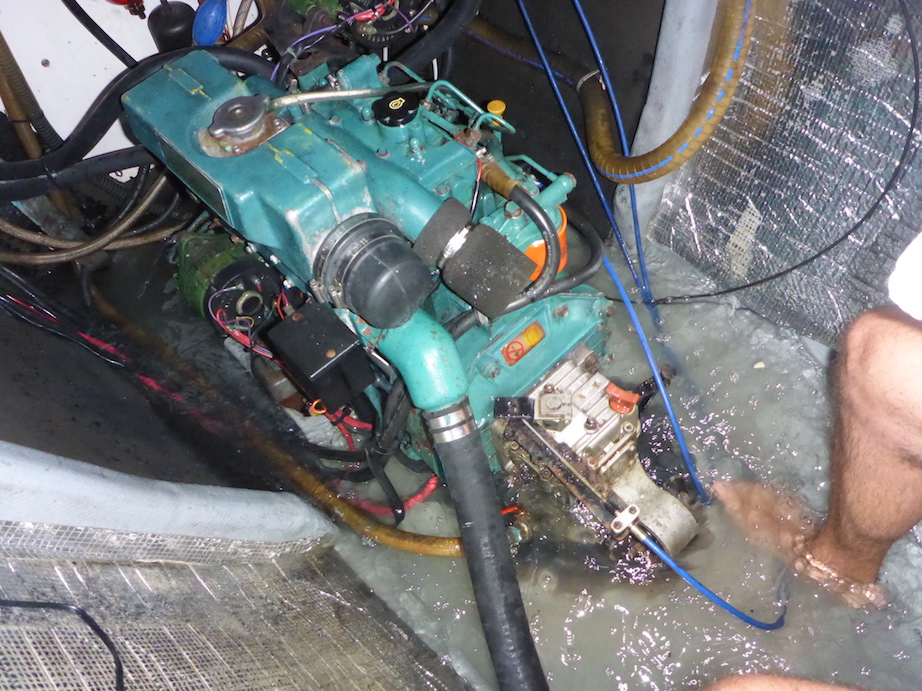

It was a starry night. The water was rising. I think I fell into a kind of stupor, the last few days had been exhausting anyway, and now I lacked the plan of how we could keep this boat up. Don and Michael had laid down in their free watch. What could they change? Anna really wanted to do something and talked about emptying the engine room with a bucket. This idea seemed pointless to me. What would we achieve if we bailed out this room? It would only fill up again! We couldn’t scoop with a bucket for 3 days, we wouldn’t be able to stand it! I decided to concentrate on the evacuation and told Anna that she could get started if she really wanted to. Armed with a bikini and a bucket, she climbed into the engine room and started pouring water out through the open hatch, while the waves threatened to roll in on her at the stern. For over an hour she worked in the sloshing oil-salt water mixture, after a while I started to accept and empty the buckets. Then Anna had actually bailed out the engine room. Together we found the cause of the leak: a break in the laminate of the hull above the skeg. The whale must have gotten caught on this fin. I tried to drive rags into the crack, but the water kept finding its way. There was nothing to be done: we would not be able to seal this leak with on-board resources. So we had to get the water under control… Since all the other pumps had failed, I converted a shower pump – and lo and behold: it managed to keep the water level in the engine room low. For the first time since the collision with the whale, we had gained some time.

It was early morning. Don and Michael were fit again. Fortunately, a spare bilge pump had been found on board, which the two wired, equipped with filters and hoses, and installed in the engine room. When the first pump was already weakening because it had become too hot in continuous operation, the new one began to take over its job. While all this was happening, we rushed east at half wind with nine, ten knots of speed. The coast was still over 300 miles away. The MRCC Lisboa inquired every 6 hours via satellite whether everything was in order. We found ourselves back in a board routine, which included the regular bailing of the engine room: Every hour the watchkeeper had to climb down there at the stern (which is quite tricky in rough seas) and turn on the pump. After about 20 minutes, the pump had to be switched off again so that it would not run hot. The wind was still freshening, which worried me. The forces acting on the hull and skeg were getting bigger and bigger. At least we were making good progress. With only one engine, the catamaran would have been miserably slow. Under sail, our daily distance was around 190 miles.

In the last night we sailed with a beam wind and good speed north of the huge Sagres traffic separation scheme towards Cape Sao Vicente. On the morning of August 28, we reached Portimão. A diver, a police boat and the surveyor of the insurance company were already waiting for us. After the hull had been examined by the diver, we went straight into the travellift and were lifted out of the water and placed ashore. When we climbed off board by means of a ladder, we were quite astonished: The side swords were shaved off. And at the stern, the broken skeg could be seen, hanging by a thread. The water ran out of the yacht there, just as it had run in before. The expert remarked laconically that, if the skeg had been completely torn away from us, it would probably not have been possible to stop us for long.